Senior Lecturer Lorene Cary on Researching the Zong Slave Ship

September 4, 2025

See this post as it originally appeared on Medium: https://lorenecary.medium.com/nece%C5%BFsity-d62448a962ab

Neceſsity

By Lorene Cary

It looks like an f, but in 18th century writing, without the crossbar, it’s a long s, which they thought neceſsary. Like mass murder on the Atlantic.

When research gets real real, there’s the need to strip down. Bracelets, watch, scarves, rings. With this volume, Documents relating a case in the Court of King’s Bench involving the ship ZONG, it was a little like taking off your earrings in the playground. In 1781, the crew of the Zong slave ship drowned 122 people taken captive in Africa. Ten more jumped. Then, when the ship reached Jamaica, the survivors were sold, and word was sent back to Liverpool, the owners’ syndicate applied for their insurers. They wanted compensation for the price of the people their crew had murdered.

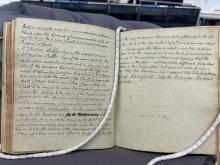

Two weeks ago I traveled to London, to the Royal Museums Greenwich, to the Caird Library, to read these documents: notes on the first trial, the appeal to the King’s bench, and letters from abolitionist Granville Sharp. They’d been copied and bound, then rebound sometime later, with part of an earlier binding affixed to the inside cover.

Neceſsity. They’d run low on water, so this desperate and brutal act had been done “of neceſsity.” Over and over the word Neceſsity. First-mate James Kelsall’s written testimony claimed that the enslaved people “would have been seized with Madness for want of water.” This mass-murder drowning was “the shortest and least painful Mode of destroying them.”

Lawyers for the insurers asked why the Zong hadn’t gone to half rations, as ships usually do in these circumstances, the better to wait for rain. No answer. And why wasn’t he called from Liverpool to testify? No one asked.

Robert Stubbs also claimed Neceſsity. The lone passenger had made such a hash of his post as governor of the Fort at Anomabo that he’d been dismissed in less than one drunken, conflict-filled year, brimming with lies. One example: He claimed the Royal African Company owed him more than 440 pounds for his service; they figured 70. But his testimony in all its disingenuous preening has been recorded for me to read nearly 250 years later; the Black peoples’ stories are not. A friend reminded me that the people below decks would have been given day names in addition to family names. I’ve found the chart. Now I imagine I could have names to call them. That’s better.

Women and children were killed first, Kelsall said, between 50 and 60. They were not sick, as the first trial alleged. Crew members caught whom they could. Each woman, each child wrestled to a cabin window and pushed out. How much beating and grabbing, dragging, slamming would it take to accomplish? Once out, how they would scream before they hit the water. Those who could not swim would die after minutes of terror. But those who could swim, what of them? What of the people on the ship who listened? And the aggressive tiger sharks and bull sharks that grew up to 200 pounds following the ships?

That first night, 29th November, people were jettisoned, as they liked to call it at trial, rather than killed. I was born 175 years later, to the day.

I went to Greenwich to answer three specific questions:

1. Is the affidavit of the first mate available in the documents? It is quoted in James Walvin’s excellent history, The Zong: a Massacre, the Law, and the End of Slavery, but I could not find it rooting through scans on my computer.

Answer: Well, a testimony from Kelsall is referred to, but not included in the bound documents in the archive. The archivists have given me a link to the archives of the Court of the Exchequer where his affidavit was filed in July of 1873, two months after the May appeal. Yet another legal proceeding. Think the bleakest possible Bleak House.

2. The protagonist of Fred D’Aguiar’s novel Feeding the Ghosts is a woman thrown overboard who hauls herself back onto the ship. Another secondary source says that the court notes mentioned a person thrown over who manages to climb back. Do the notes actually say so?

Answer: Yes, but. It’s just one line, written in two places, but it says “…& one Man more that had been cast overboard alive, but escaped, it seems, by laying hold of a rope, which hung from the Ship onto the water, & thereby without being perceived regained the Ship, secreted himself, & was saved…”

Early research is a mess, whether for a book or a play or libretto. Everything is complicated, details scattered. Unreliable narrators saying anything they think…necessary. And Western storytelling presses in from all sides, nudging the mind to construct from the mess story structures, even clichés we know and like. Of Neceſsity. Once Upon a Time. Bad things are punished. People died, but not in vain. God never gives more than we can bear.

My own memory tries to keep track as I read the also messy document, probably organized by Granville Sharp. But the lawyers lie — I can see that now as I read pages, here, in person. They bring in distractions, and they obfuscate and repeat half-truths so often you start to believe them. Then another lawyer comes in and contradicts. One of the three judges asks a question. My back-of-the-brain video shuts down, erases, shoots from another angle. I walk out for air and see tourists eating ice cream. Or down the hall where low light glints off the glass box that holds a display of shackles and leg irons, a wide-mouth blunderbuss gun, and a whip braided from the hide of a hippo.

3. One secondary source reports an enslaved man who had picked up English telling a crew member that the captives said they will do without the water and food. Just don’t throw us over.

Answer: Yes. From First Officer James Kelsall’s affidavit. He states that one captive man had learned enough English to tell him that the people below understood that the killings had to do with the ship’s lack of resources, that there was no need to throw them overboard to certain death in the ocean. They could do without.

Now, I need to study the affidavit to confirm, as historian James Walvin writes, that the man speaking was indeed about to be killed. They brought the men up onto the deck, shackled? Or did they bring them up and shackle them there? Or add more shackles? Did they train the blunderbuss guns on them? Might they have shot someone to start, as crews did to show that resistance was useless? Some ships had nets to keep captives from drowning themselves. Did this ship have one that had to be pulled in to allow the wholesale killing?

Oh, and I need to confirm that after he said this, they did throw him in anyway — was it Kelsall who did it?

Each new story requires growing into the person capable of telling it. That’s what this trip to London was meant to help me do — the short-notice cheap ticket, the stay in the hostel dormitory, like the oldest grad student in the world. It aims me toward the Zong, its facts and ocean-wide gaps, scholars who have studied it, the trade and middle passage, and my capacity to let it wash through me. It feels like sacrilege to force these lives and deaths into a story. But it’s a kind of ancestor worship. This is what I know, or think I know, to do.

Because that man who “secreted himself” back onto the ship, the dying countrymen in the churning waters; the women and children shoved through cabin windows; the brilliant man who had somehow learned enough English to plead for the lives of his captured and brutalized cohort, before he was thrown, shackled, to his death: those people, whose molecules nourished the ecosystem in the Caribbean where my great-grandfather dived for “sea eggs” as a boy less than 100 years later. They deserve a telling worthy of them.

Featuring Lorene Cary

Department of English

Department of English