English 016/ Italian/ COML/ GSWS Remember Me: Premodern Women

Premodern women, like all women, wondered what would remain of them in the future. How, if at all, would they be remembered? Could a woman’s life, historical and biological, become a life, a written record to survive the passage of time? And, if so, in what literary genre would their life be told? Most women found that their best hope of being remembered lay in behaving badly: that is, in ways that would provoke someone to write. They also found that the rise of universities, a great leap forward for men, brought a corresponding decrease in women’s educational opportunities; Virginia Woolf still finds herself being yelled at on the college lawns of Oxbridge in the 1920s. In this course we will see how a range of courageous, enterprising, and ingenious women met the challenges of their time, in England and Italy, between the years 1100-1700.

We begin by celebrating four women who achieved great things, and lived remarkable lives, before this time of established university culture. Hildegard of Bingen was a musician, natural scientist, cosmographer, dramatist, fashion designer, preacher, and author. Christina of Markyate was a runaway bride, Marie de France a genius romancer and fabulist (her Bisclavret is a werewolf story), and Heloise the most famous lover of the European Middle Ages and the author of great letters.

There are shrines to Rita of Cascia (c. 1381-1457) across the world, including one in Kerala, India. Her national shrine in the US is at 1166 South Broad Street, Philadelphia; we might make a visit, or pilgrimage. St Rita was forced into an arranged marriage and endured eighteen years of abuse; she attempted to reform her violent husband, and also the vendetta culture that eventually killed him. Angela of Foligno (1248-1309), who had several children before turning religious at around age 40, refused to live in seclusion but lived communally, with other women.

The two most powerful and influential women of fourteenth-century Europe, and the only two to be declared saints, lived in Rome, one after the other. Speakers of truth to power, they were just as famous in their lifetimes, and long after, as the poets known in Italy as the tre corone, or three crowns: Dante, Boccaccio, and Petrarch. The East Anglian woman Margery Kempe went looking for the living spaces of Bridget of Sweden when she visited Rome; closer to home, she visited the brilliant mystic Julian of Norwich, who said all shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well. Julian, a woman with a man's name, rewrote the story of the Fall in Eden and could not believe that God might damn anyone for all eternity.

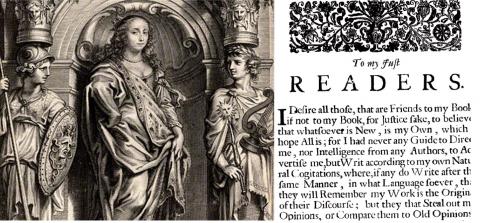

Gaspara Stampa (1523-1554) and Veronica Franco (1546-1591) were brilliant Venetian courtesans, educated and accomplished women who maintained liaisons with aristocratic men. In her Rime di Madonna Gaspara Stampa, Gaspara establishes herself as a poet like Petrarch, but female, triumphing over difficulties (and her last male lover). Franco, also a cortigiana onesta ("intellectual sex worker"), came to command a high place in important Venetian literary circles. Isabella Witney (active 1566-1573) published her own works, keen to showcase her talents as a housekeeper and lady's lady, and to avoid falling through the floor into prostitution or jail. Whitney, a woman of slender means and humble background, uses print to try and advance her own career, whereas the aristocratic Mary Sidney (1561-1621) restricts her writings to an élite few, in manuscript. She lives privately at Wilton, in a great house that was once a great convent, reading psalms, like nuns long before her; her psalmic verse marries brilliant poetic experimentalism with Calvinist terror. Elizabeth Carey writes the first closet drama in English on Miriam, Queen of Jewry; she then disgraces herself by converting to Catholicism and mothering four brilliant daughters (who copy and conserve the text of Julian of Norwich). This they must do abroad, as Catholic nuns; Mary Ward, a Catholic from Yorkshire, joins them in exile, but founds an international order for women who will not be enclosed. Her vast archive, closed to the public for centuries, is now available, including her writings in Italian as Maria della Guardia. Aemilia Bassano, daughter of an Italian musician, publishes a remarkable collection of verse as Aemilia Lanyer that includes the first English country-house poem. This explores the reverse of nun-like enclosure: women happily gathered in female society must soon be scattered, and take on new names, following the iron logic of the marriage market.

Sarra Copia Sallam (1592-1641) grew up Jewish in Venice and learned ancient Greek, Latin, and Hebrew. In 1618 she read a play called Esther by Ansaldo Ceba, a diplomat who had become a monk. This led to a long letter exchange; Sarra admits to sleeping with Esther. Accused of heresy, she wrote a book to defend herself, resisting all attempts to convert her from Judaism. Lady Hester Pulter (1595/6-1678), born in Dublin, had fifteen children and outlived all but two of them. Her Unfortunate Florinda. reweaves legends about the Muslim conquest of Spain, channels contemporary anxieties about "turning Turk," and addresses issues of rape. Penn's Van Pelt owns a copy of the vast, lavishly-funded tome of plays by Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle (1623-1673); we will make a visit to special collections in order to see this and other precious materials. Cavendish eagerly keeps up with contemporary science, writes feminist science fiction, and strategically exploits the power of her own beauty. Like Galileo, she makes good use of telescopes, but to quite different ends. Cavendish continues to ponder the possibilities of all-female society, in both her Convent of Pleasure and, more seriously, her Female Academy. Such longing for female places of learning endures, in various forms, through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

These premodern texts may be studied in and of their own time, or as they emerge into print and public consciousness in later centuries, including our own.

The first assignment will ask you to write your own life story in the third person as a short (500 word) saint’s life, an exercise in literary genre as well as self-expression (and a pass/fail writing tune up). The second and third assignments will be short essays and the fourth a longer one, with some research component; there will be no midterm or final.

Department of English

Department of English